If The Little Traveler has a secret weapon, it's Joe Greenberg. He's our behind-the-scenes guy who keeps operations running smoothly and makes us smile every day. You might also recognize him as our chief photographer, the Easter bunny, Tie-dye Santa, and Leprechaun Joe.

While we celebrate the 242nd anniversary our nation's independence, we want to honor those who've helped preserve our freedom throughout the course of the United States' history. Joe is in that group. He served in the US Navy and was on duty the day World War II ended. Some of you may remember that in 2015, he was chosen for an Honor Flight after being nominated by the Atrium Cafe's manager and chef, David Bogash.

As if we needed another reason to love Joe.

Joe returning from his Honor Flight.

Joe Greenberg's military journey started in 1944 during World War II. As a young man just old enough to enlist, he wanted to be part of the Navy. But back then, he was told that because he wore glasses, he wasn't eligible for that branch of the military. So, he waited for the draft.

When he showed up for his physical, as he was standing around with a bunch of other guys wearing only their skivvies, an official came in and announced that some men were needed for the Navy. Joe saw his opportunity and took it. He was re-directed to the Navy, but when he showed up for that physical, his papers were rejected—because he wore glasses—and he was sent to an officer to let him know he was ineligible.

Following instructions, teen-aged Joe Greenberg reported to the officer, who asked, "Do you see these gold bars on my shoulders? Do you know what they mean?" Without waiting for an answer, he informed young Greenberg: "They mean I'm in charge and you're in the Navy."

So, Joe got back in line, and when he reached the sailor who'd rejected him earlier, he told him of the officer's orders. The sailor took Joe's papers and tossed them into the air, saying, "We've lost the war. Now we're taking blind people."

Picking up those scattered papers marked the start of Joe's service with US Navy.

His first assignment was torpedo training in Newport, RI, and then he went on to amphibious landing training in Long Island, NY. His unit was preparing to go to the war zone to transport men and tanks onto the beaches. After completing training, they were sent to San Bruno, CA to await deployment. These young men were prepared and eager to serve, but this was also a time of trepidation. They knew of the tremendous loss of US lives in previous military campaigns, including the Battle of Guadalcanal and the Battle of Iwo Jima. The Japanese were fierce and tenacious fighters.

While they prepared to join the fray, Joe and his fellow sailors received news of the first atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima. Their primary question was, "What's an atomic bomb?"

They were told it had "the force of 1000 boxcars full of dynamite," so they knew it was big, but they had no frame of reference to understand exactly how big. It was only after the war ended and they read details of the aftermath that they grasped the atom bomb's full destructive powers. But at the time, they didn't realize this bomb and the one that soon followed in Nagasaki would signify the end of the war.

Through newspapers, Joe and his fellow sailors learned that Japan had surrendered and the war was over. In a flash, they went from fear and trepidation to joy and jubilation. Sailors and soldiers were given liberty, so Joe and legions of others descended on San Francisco to celebrate.

Oh, the things Joe saw. It was a massive party, a release from the pall of war that had been hanging heavily over the country for years. And for these men, who'd lost many friends to the battlefield during the last four years, it was a reprieve from heading into a heated war zone filled with terrors. The party became a bit more "jubilant" than anticipated (according to Joe, "The Japanese probably would've done less damage than the servicemen did that day"), enough so that the next day, they were all restricted to their respective bases.

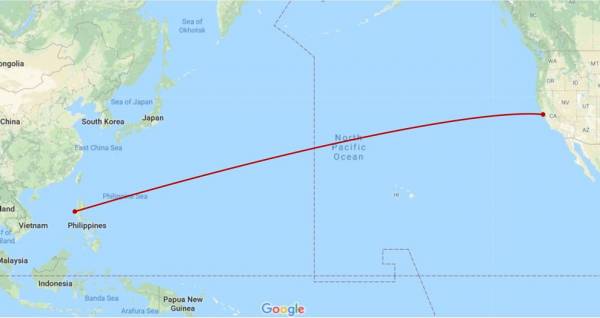

There was still work to be done. While service-people in the field headed home, Joe and his unit headed out. They were sent to the Subic Bay Naval Base in the Philippines. Just because the war had ended, it didn't mean there was no danger. As Joe explains, "There were Japanese subs still out there that didn't know the war was over." So they sailed carefully, always watching for enemy submarines, from the California coast all the way to the Philippines without stopping.

Landing docks had been destroyed during the war, so Joe's amphibious landing training was essential. He and the rest of his unit carried food supplies and equipment from ships straight onto the beach in Loading Craft Tanks (LCTs) big enough to hold four land tanks. The US sailors met Japanese prisoners of war when they came on board to help with unloading. "They didn't speak English; we didn't speak Japanese, but we were able to communicate what needed to be done," Joe explains. He also says the Japanese were very helpful at fixing engines and other mechanical glitches.

It's easy to forget how young these men were who served their country so well. The officer in charge of Joe's unit was all of 22 years old. His men were teenagers. While we typically think of crisp white uniforms or dark blue jackets with brass buttons when it comes to the Navy, this crew wore "T-shirts, shorts, and shower clogs," according to Joe. He fondly calls his group "McHale's Navy."

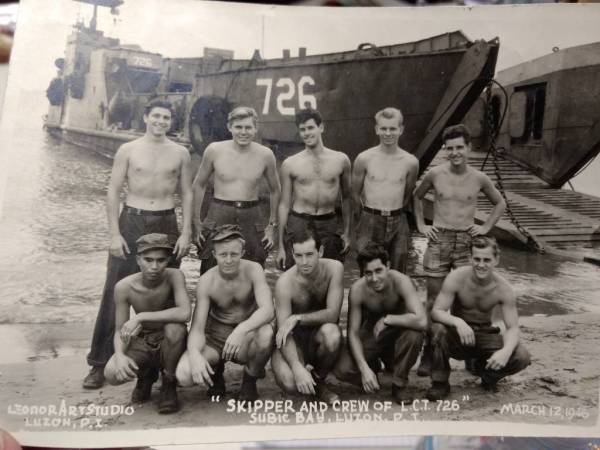

Skipper and Crew of LCT 726 on base in the Philippines. (Joe is back row, center)

When it came time to unload the shipment of beer, and it made the rounds from LCT to LCT to LCT...would you like to take bets on whether or not all the cases made it to shore? This 4th of July, we raise a can to Joe, his unit, and all the young sailors and soldiers who've made it possible for us to remain free. Cheers!